The documents and materials published on this website were collected, researched, and prepared with advice from experts, as a part of a Government-commissioned project. The contents of this website do not reflect the views of the Government. Links to external sites (domains other than https://www.cas.go.jp) are not under the management of this site. For linked websites, please check with the organization/group that manages the website for the link in question.

Comprehensive issues

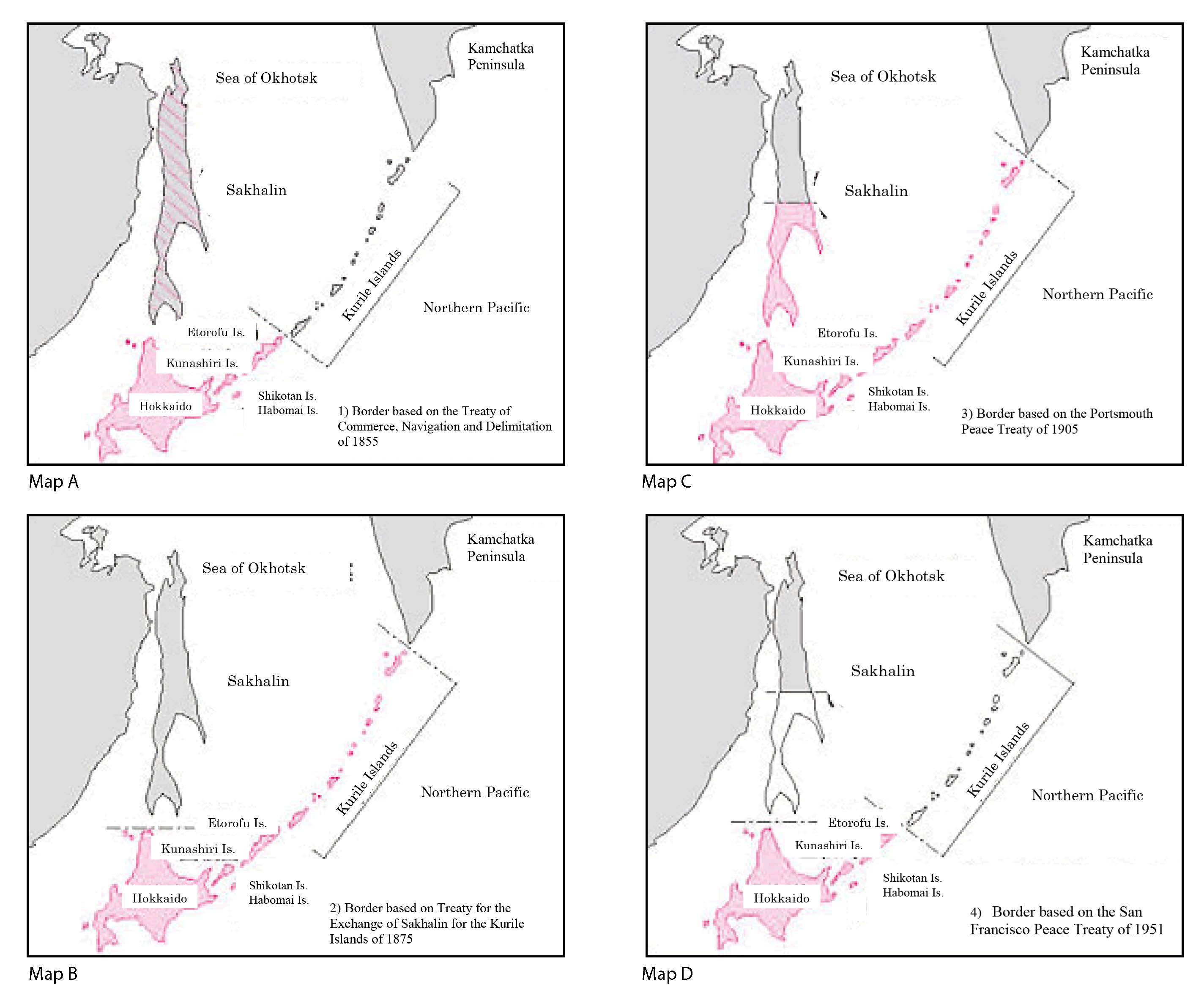

5. Scope of “the Kurile Islands” to which Japan renounced right, title and claim under Article 2(c) of the San Francisco Peace Treaty

It is no exaggeration to say that this is the most important point of debate in the Northern Territories issue from the perspective international law.Article 2(c) of the San Francisco Peace Treaty stipulates that, “Japan renounces all right, title and claim to the Kurile Islands.”

Renunciation constitutes a unilateral legal act (acte juridique unilatéral) under international law (other unilateral legal acts include unilateral promise, recognition, protest, and notification).2 Renunciation may also be provided for in treaties, and Japan’s act of renunciation under the San Francisco Peace Treaty is one of these.

What should first be observed with regard to Japan’s renunciation is that Japan did not cede the Kurile Islands to the Soviet Union. This renunciation is unnamed, meaning that the party to which the renunciation is addressed has to date not been specified. That is the reason why, on official Japanese maps, the islands north of Uruppu Island, right and title to which Japan renounced, are not colored the same as those of the Soviet Union / Russia.

The first thing that should be noted with regard to the overall interpretation of the San Francisco Peace Treaty is the existence of the principle of “contra proferentem” (against the offeror), which is a basic principle of treaty interpretation. There are also judgments that relied on this principle, including the Permanent Court of International Justice ruling on the “Case concerning the Payment in Gold of Brazilian Federal Loans Contracted in France” (1929).3 With regard to this point, it is important to note what Kumao Nishimura, Director-General of the Treaties Bureau of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, stated in his response to the House of Councillors’ Special Committee on the Peace Treaty and the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty on November 7, 1951. “As a principle of treaty interpretation, if any doubts should be raised as to the interpretation of a treaty that imposes obligations, the principle is that it should be taken to be borne lightly by the obligated party. ... In our view, we seek to adhere to the principle of international law that if any doubts should be raised about the interpretation of Japan’s obligations arising from this peace treaty, then it should be borne lightly by the obligated party.”

This interpretation criterion is also consistent with the interpretation criterion relating to the extent of renunciation. The following two international arbitral decisions set out important interpretive principles for cases where the extent of renunciation is unclear. (1) The Arbitral Award of the Affaire Campbell (1931, UK v. Portugal) ruled that under international law, renunciations are never presumed and as they constitute the abandonment of a right, they are always subject to strict interpretation.4 (2) The Arbitral Award of the Indo-Pakistan Western Boundary (Rann of Kutch) case ruled that statements on the British side to the effect that the wetland (Rann) of the state of Kutch may amount to a voluntary relinquishment of potential British territorial rights, and any uncertainty in this respect ought properly to be resolved in favor of Pakistan. The reason was that the claim made by Kutch must be interpreted restrictively to the disadvantage of the claiming party and the statements issued by the British authorities must be understood in like fashion and cannot in the circumstance be extensively interpreted.5 Similar observations are made in academic papers. In Les actes juridiques unilatéraux en droit international public, Suy observes that, “…as the effect of the renunciation is the extinction of right, its intention should be interpreted strictly and, in case of doubt, it should be interpreted in a sense favorable to the renouncing party.” 6

The position of the Government of Japan is that the scope of the Kurile Islands to which Japan renounced its right, title and claim under the San Francisco Peace Treaty is limited to the islands north of Uruppu Island, and that this point is beyond question. However, even if it were to be assumed that some question remained about the scope of the renunciation by Japan of the Kurile Islands, the rules of international law regarding the interpretation of the scope of renunciation suggest a narrow interpretation in favor of the party making the renunciation. In other words, the scope of the “Kurile Islands” to which Japan renounced its right, title and claim are those islands north of and including Uruppu Island, and do not include Etorofu Island, Kunashiri Island, Habomai Islands, and Shikotan Island, is a reasonable interpretation in accordance with international law.

Note 2

With regard to unilateral legal acts, see Kazuhiro Nakatani, Kokka ni yoru Ippo-teki Ishi Hyomei to Kokusaiho (Unilateral Declaration of Intent by a State and International Law) (Shinzansha, 2021).

Note 3

PCIJ Ser. A, No.21, p.115.

Note 4

RIAA, vol. II, p.1156.

Note 5

RIAA, vol. XVII, p. 565.

Note 6

Eric Suy, Les actes juridiques unilatéraux en droit international public (LGDJ, 1962), p. 185.

6. The Yalta Agreement

In the Yalta Agreement of February 11, 1945 (a secret agreement between General Secretary Stalin of the Soviet Union, President Roosevelt of the United States, and Prime Minister Churchill of the United Kingdom), the three leaders agreed that, “The Kurile Islands shall be handed over to the Soviet Union.”

Under international law, the Yalta Agreement remains a non-binding agreement (soft law, a gentlemen’s agreement) that is not legally binding. Even in the case of a legally binding treaty, “a treaty binds the parties and only the parties; it does not create obligations for a third state” (pacta tertiis nec nocent nec prosunt). Therefore, the Yalta Agreement, which is no more than a non-binding agreement, has no opposability toward third parties whatsoever, and therefore does not bind Japan as a third state at all. Moreover, the Yalta Agreement cannot in any way serve as a legal basis for the transfer of territory, given that it is merely an interim agreement stating common objectives shared among the three leaders.

On this point, in his response to the House of Councillors’ Special Committee on the Peace Treaty and the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty on October 29, 1951, Kumao Nishimura, Director-General of the Treaties Bureau of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, stated the following. “The Yalta Agreement is, essentially, a political commitment undertaken by a small number of countries regarding the disposition of a part of Japan’s territory, and whether and how this commitment is ultimately realized through inclusion in a peace treaty shall depend on negotiations among the Allied nations until such a time as a peace treaty is concluded. Accordingly, I believe that the Government of Japan is not mistaken in its existing position that it is not bound by the Yalta Agreement in any way.”

7. Interpretation of paragraph 9 of the Japan-Soviet Joint Declaration

Paragraph 9 of the Japan-Soviet Joint Declaration, which was signed on October 19, 1956 and entered into force on December 12, 1956, states that, “Japan and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics agree to continue, after the restoration of normal diplomatic relations between Japan and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, negotiations for the conclusion of a peace treaty. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, desiring to meet the wishes of Japan and taking into consideration the interests of Japan, agrees to hand over to Japan the Habomai Islands and the island of Shikotan. However, the actual handing over of these islands to Japan shall take place after the conclusion of a peace treaty between Japan and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.”

With respect to the above paragraph, the following interpretation is compatible with provisions regarding the interpretation of conventions and treaties (stipulated in Articles 31 to 33 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties and has become customary international law).

Firstly, that through this Declaration the Soviet Union agrees to hand over to Japan the Habomai Islands and Shikotan Island, and that this provision is immediately binding on the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation, which is the successor state to the Soviet Union.

Second, “hand over” does not mean transfer of territorial title, but rather physically handing over the islands.

Thirdly, although the actual handing over of the Habomai Islands and Shikotan Island is stipulated to take place after the conclusion of a peace treaty, this refers to an actual date for fulfilment of obligations that have accrued in advance. This does not mean that the obligation to hand over the islands will not arise until such a time as a peace treaty is concluded, rather that the obligation to hand over the islands arose at the very latest on December 12, 1956, which is the date the Japan-Soviet Joint Declaration entered into force.

Fourthly, the paragraph makes no mention of Etorofu Island and Kunashiri Island. The Joint Declaration therefore has no influence on the dispute over the territorial rights to these two islands.

8. The struggle to restore the rule of law in the international community

The illegal occupation of Japan’s Northern Territories by the Soviet Union that took place from August 28 to September 5, 1945, was, like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, a serious violation of international law that constituted “a unilateral change of the status quo by force”. The return of the Northern Territories is not just an issue of restoring Japan’s subjective rights, but is also an issue of restoring the “rule of law in the international community”. Given that the renunciation of right, title and claim to the Kurile Islands was made under the terms of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, the States Parties to the Treaty should extend their support to Japan in its struggle to restore “the rule of law in the international community”.

https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/area/hoppo/hoppo_keii.html

Senkaku Islands

Research and Commentary Site

- I Comprehensive issues

- II Commentary on themes by historical period

- III Analysis of claims by other countries